Immunotherapy Basics

Gain in-depth knowledge about immunotherapy and the unique role your immune system plays in preventing, controlling, and eliminating a variety of cancers.

What Is Immunotherapy?

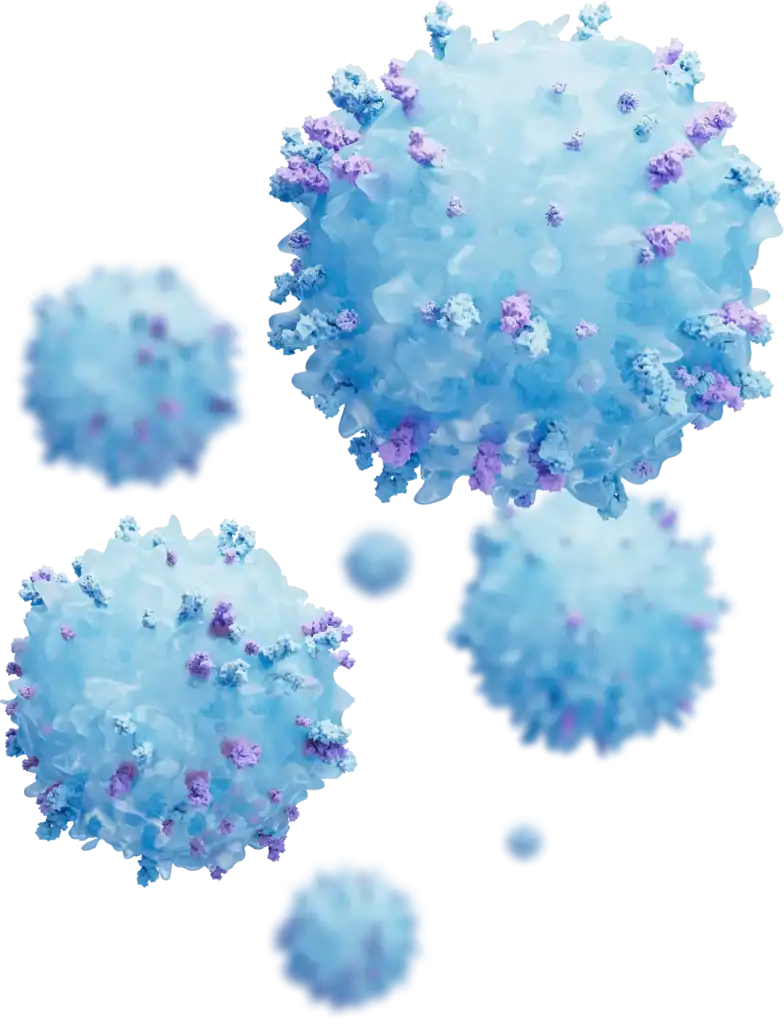

Immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses the power of your body’s own immune system to prevent, control, and eliminate cancer. Immunotherapy is sometimes also called immuno-oncology.

There are several types of immunotherapies, and each works differently to enhance your immune system’s response to cancer. This can involve providing your body with additional tools to enhance your immune response, such as proteins or antibodies, and/or boosting your existing immune cells to help them eliminate cancer. Types of immunotherapy include immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), bispecific antibodies, adoptive cell therapies, non-ICI immunomodulators like cytokines, oncolytic viruses, and cancer vaccines.

Many immunotherapy treatments can also be used in combination with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or other targeted therapies to prevent, manage, and treat different cancers.

Immunotherapy can:

Educate the immune system to recognize and attack specific cancer cells

Provide the body with additional components to enhance the immune response

Boost immune cells to help them eliminate cancer

Unleashing the power of the immune system is a smart way to fight cancer.

1

It’s Precise

The immune system is precise, so it is possible for it to target cancer cells exclusively while sparing healthy cells.

2

It’s Dynamic

The immune system can adapt continuously and dynamically, just like cancer does, so if a tumor manages to escape detection, the immune system can re-evaluate and launch a new attack.

3

It Remembers

The immune system’s “memory” allows it to remember what cancer cells look like, so it can target and eliminate the cancer if it returns.

Why Immunotherapy

Immunotherapies have been approved in the United States and elsewhere to treat a variety of cancers and are prescribed to patients by oncologists. These approvals are the result of years of research and testing designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of these treatments. Immunotherapies are also available through clinical trials, which are carefully controlled and monitored studies involving patient volunteers.

Immunotherapy doesn’t always work for every patient, and certain types of immunotherapy are associated with potentially severe but manageable side effects. Scientists are developing ways to determine which patients are likely to respond to treatment and which aren’t. This research is leading to new strategies to expand the number of patients who may potentially benefit from treatment with immunotherapy.

Although scientists haven’t yet mastered all the immune system’s cancer-fighting capabilities, immunotherapy is already helping to extend and save the lives of many cancer patients. Immunotherapy holds the potential to become more precise, more personalized, and more effective than current cancer treatments—and potentially with fewer side effects. Learn more about how you can support new breakthroughs in cancer immunotherapy research.

Many cancer patients and caregivers may be familiar with traditional treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation. Several important features of immunotherapy, a form of cancer treatment that uses the power of the body’s immune system to prevent, control and eliminate cancer, make for a more specific answer to cancer.

Cancer immunotherapy can work on many different types of cancer.

Immunotherapy enables the immune system to recognize and target cancer cells, making it a universal answer to cancer.

The list of cancers that are currently treated using immunotherapy is extensive. See the full list of immunotherapies by cancer type.

Immunotherapy has been an effective treatment for patients with certain types of cancer that have been resistant to chemotherapy and radiation treatment (e.g., melanoma).

Cancer immunotherapy offers the possibility for long-term cancer remission.

Immunotherapy can train the immune system to remember cancer cells. This “immunomemory” may result in longer-lasting remissions.

Clinical studies on long-term overall survival have shown that the beneficial responses to cancer immunotherapy treatment are durable—that is, they may be maintained even after treatment is completed.

Immunotherapy has been an effective treatment for patients with certain types of cancer that have been resistant to chemotherapy and radiation treatment (e.g., melanoma).

Cancer immunotherapy may not cause the same side effects as chemotherapy and radiation.

Cancer immunotherapy is focused on the immune system and may be more targeted than conventional cancer treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation.

Side effects vary according to each therapy and how it interacts with the body. Conventional cancer treatments have a direct effect of a chemical or radiological therapy on cancer and healthy tissues, which may result in common side effects such as hair loss and nausea.

Side effects of cancer immunotherapy may vary depending on which type of immunotherapy is used. Potential side effects relate to overstimulation or misdirection of the immune system and may range from minor symptoms of inflammation (e.g., fever) to major conditions similar to autoimmune disorders.

There are pros and cons to every cancer treatment. Speak with your oncology care team about immunotherapy and what is the best treatment plan for you.

Get more information

Resources, Answers, and Support

Organizations that provide support and reliable answers for cancer patients and their loved ones

ImmunoGlossary

A comprehensive glossary that will help explain some

of the terms you’ll come across on our website

Frequently Asked Immunotherapy Questions

What types of cancers can immunotherapy treat?

Immunotherapy has the potential to treat all cancers.

Immunotherapy enhances the immune system’s ability to recognize, target, and eliminate cancer cells, wherever they are in the body, making it a potential universal answer to cancer.

Immunotherapy has been approved in the U.S. and elsewhere as a first-line of treatment for several cancers, and may also be an effective treatment for patients with certain cancers that are resistant to prior treatment. Immunotherapy may be given alone or in combination with other cancer treatments. As of December 2019, the FDA has approved immunotherapies as treatments for nearly 20 cancers as well as cancers with a specific genetic mutation

Does immunotherapy have any side effects?

Immunotherapy may be accompanied by side effects that differ from those associated with conventional cancer treatments, and side effects may vary depending on the specific immunotherapy used. In most cases, potential immunotherapy-related side effects can be managed safely as long as the potential side effects are recognized and addressed early.

- Cancer immunotherapy treats the patient—by empowering their immune system—rather than the disease itself like chemotherapy and radiation. Patients may be tested for biomarkers that may indicate whether cancer immunotherapy would be an effective treatment.

- Side effects of immunotherapy may results from stimulation of the immune system and may range from minor inflammation and flu-like symptoms, to major, potentially life-threatening conditions similar to autoimmune disorders.

- Common side effects may include but are not limited to skin reactions, mouth sores, fatigue, nausea, body aches, headaches, and changes in blood pressure.

Conventional cancer treatments also have a range of side effects with a wide range of severity.

The goal of surgery is to remove the cancerous tumor or tissue and varies according to the type of surgery performed. Common side effects may include but are not limited to pain, fatigue, swelling, numbness, and risk of infection.

Chemotherapy is intended to target fast-growing cancer cells, so it may damage other fast-growing normal cells in your body. Common side effects may include but are not limited to hair loss, nausea, diarrhea, skin rash, and fatigue.

Radiation uses radioactive particles to destroy cancer cells in a localized area, so it may damage other healthy cells in that area. Side effects may be associated with the area of treatment, such as difficulty breathing when aimed at the chest, or nausea when aimed at the stomach. Skin problems and fatigue are common.

How long does immunotherapy last?

Cancer immunotherapy offers the possibility for long-term control of cancer.

Immunotherapy can “train” the immune system to remember cancer cells. This “immunomemory” may result in longer-lasting and potentially permanent protection against cancer recurrence.

Clinical studies on long-term overall survival have shown that the beneficial responses to cancer immunotherapy treatment can be durable—that is, they continue even after treatment is completed.

How long has immunotherapy been used as a cancer treatment?

Cancer immunotherapy originated in the late 1890s with a cancer surgeon named Dr. William B. Coley (1862–1936). He discovered that infecting cancer patients with certain bacteria sometimes resulted in tumor regression and even some complete remissions. Advances in cancer immunology since Coley’s time have revealed that, in patients that responded to his treatment, his bacterial toxin therapy stimulated their immune systems to attack the tumors.

While Coley’s approach was largely dismissed during his lifetime, his daughter, Helen Coley Nauts, discovered his old notebooks and founded the Cancer Research Institute in 1953 to support research into his theory. In 1990, the FDA approved the first cancer immunotherapy, a bacteria-based tuberculosis vaccine called Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), which was shown to be effective for patients with bladder cancer.

What is the relationship between cancer and the immune system?

While many of our cells grow and divide naturally, this behavior is tightly controlled by a variety of factors, including the genes within cells. When no more growth is needed, cells are told to stop growing.

Unfortunately, cancer cells acquire defects that cause them to ignore these stop signals, and they grow out of control. Because cancer cells grow and behave in abnormal ways, this can make them stand out to the immune system, which can recognize and eliminate cancer cells through a process called immunosurveillance.

However, this process isn’t always successful. Sometimes cancer cells develop ways to evade and escape the immune system, which allows them to continue to grow and metastasize, or spread to other organs. Therefore, immunotherapies are designed to boost or enhance the cancer-fighting capabilities of immune cells and tip the scales in the immune system’s favor.

What types of immunotherapy treatments are there?

Immunotherapy treatments can be broken down into five types:

- Targeted antibodies are proteins produced by the immune system that can be customized to target specific markers (known as antigens) on cancer cells, in order to disrupt cancerous activity, especially unrestrained growth. Some targeted antibody-based immunotherapies, known as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), are equipped with anti-cancer drugs that they can deliver to tumors. Others, called bi-specific T cell-engaging antibodies (BiTEs), bind both cancer cells and T cells in order to help the immune system respond more quickly and effectively. All targeted antibody therapies are currently based on monoclonal antibodies (clones of a parent bonding to the same marker(s)).

- Adoptive cell therapy takes a patient’s own immune cells, expands or otherwise modifies them, and then reintroduces them to the patient, where they can seek out and eliminate cancer cells. In CAR T cell therapy, cancer-fighting T cells are modified and equipped with specialized cancer-targeting receptors known as CARs (chimeric antigen receptors) that enable superior anti-cancer activity. Natural killer cells (NKs) and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) can also be enhanced and reinfused in patients.

- Oncolytic virus therapy uses viruses that are often, but not always, modified in order to infect tumor cells and cause them to self-destruct. This can attract the attention of immune cells to eliminate the main tumor and potentially other tumors throughout the body.

- Cancer vaccines are designed to elicit an immune response against tumor-specific or tumor-associated antigens, encouraging the immune system to attack cancer cells bearing these antigens. Cancer vaccines can be made from a variety of components, including cells, proteins, DNA, viruses, bacteria, and small molecules. Some versions are engineered to produce immune-stimulating molecules. Preventive cancer vaccines inoculate individuals against cancer-causing viruses and bacteria, such as HPV or hepatitis B.

- Immunomodulators govern the activity of other elements of the immune system to unleash new or enhance existing immune responses against cancer. Some, known as antagonists, work by blocking pathways that suppress immune cells. Others, known as agonists, work by stimulating pathways that activate immune cells. Checkpoint inhibitors target the molecules on either immune or cancer cells, telling them when to start or stop attacking a cancer cell. Cytokines are messenger molecules that regulate maturation, growth, and responsiveness. Interferons (IFN) are a type of cytokine that disrupts the division of cancer cells and slows tumor growth. Interleukins (IL) are cytokines that help immune cells grow and divide more quickly. Adjuvants are immune system agents that can stimulate pathways to provide longer protection or produce more antibodies (they are often used in vaccines, but may also be used alone).

What is the difference between immunotherapy and chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy is a direct form of attack on rapidly-dividing cancer cells, but this can affect other rapidly dividing cells including normal cells. When patients respond, the treatment’s effects happen immediately. These direct effects of chemotherapy, however, last only as long as treatment continues.

Immunotherapy treats the patient’s immune system, activating a stronger immune response or teaching the immune system how to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Immunotherapy may take more time to have an effect, but those effects can persist long after treatment ceases.

Who can receive immunotherapy? What immunotherapies are approved for standard care?

As of March 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had approved over 60 immunotherapies that together cover almost every major cancer type:

- Aldesleukin (immunomodulator) for kidney cancer and melanoma

- Alemtuzumab (targeted antibody) for leukemia

- Amivantamab (bispecific antibody) for lung cancer

- Atezolizumab (checkpoint inhibitor) for bladder, liver, and lung cancer, and melanoma

- Avelumab (checkpoint inhibitor) for bladder, kidney, and skin cancer (Merkel cell carcinoma)

- Axicabtagene ciloleucel (CAR T cell therapy) for lymphoma

- Bacillus Calmette-Guérin [BCG] (vaccine) for bladder cancer

- Belantamab mafodotin-blmf (antibody-drug conjugate) for multiple myeloma

- Bevacizumab (targeted antibody) for brain, cervical, colorectal, kidney, liver, lung, and ovarian cancer

- Blinatumomab (bi-specific T cell-engaging antibody) for leukemia

- Brentuximab vedotin (antibody-drug conjugate) for lymphoma

- Brexucabtagene autoleucel (CAR T cell therapy) for leukemia and lymphoma

- Cemiplimab (checkpoint inhibitor) for lung cancer and skin cancer (basal cell carcinoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma)

- Cetuximab (targeted antibody) for colorectal and head and neck cancer

- Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (CAR T cell therapy) for multiple myeloma

- Daratumumab (targeted antibody) for multiple myeloma

- Denosumab (targeted antibody) for sarcoma

- Dinutuximab (targeted antibody) for pediatric neuroblastoma

- Dostarlimab (checkpoint inhibitor) for uterine (endometrial) cancer

- Durvalumab (checkpoint inhibitor) for lung cancer

- Elotuzumab (targeted antibody) for multiple myeloma

- Enfortumab vedotin-ejfv (antibody-drug conjugate) for bladder cancer

- Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (antibody-drug conjugate) for leukemia

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, or GM-CSF (immunomodulator) for neuroblastoma

- Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant) (preventive vaccine) for liver cancer

- Human Papillomavirus Quadrivalent (Types 6, 11, 16, 18) Vaccine, Recombinant (preventive vaccine) for cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer

- Human Papillomavirus 9-valent Vaccine, Recombinant (preventive vaccine) for cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and throat cancer

- Human Papillomavirus Bivalent (Types 16 and 18) Vaccine, Recombinant (preventive vaccine) for cervical cancer

- Ibritumomab tiuxetan (antibody-drug conjugate) for lymphoma

- Idecabtagene vicleucel (CAR T cell therapy) for multiple myeloma

- Imiquimod (immunomodulator) for skin cancer (basal cell carcinoma)

- Inotuzumab ozogamicin (antibody-drug conjugate) for leukemia

- Interferon alfa-2a (immunomodulator) for leukemia and sarcoma

- Interferon alfa-2b (immunomodulator) for leukemia, lymphoma, and melanoma

- Ipilimumab (checkpoint inhibitor) for colorectal, liver, and lung cancer, and melanoma and mesothelioma

- Isatuximab (targeted antibody) for multiple myeloma

- Lisocabtagene maraleucel (CAR T cell therapy) for lymphoma

- Loncastuximab tesirine (antibody-drug conjugate) for lymphoma

- Margetuximab (targeted antibody) for breast cancer

- Mogamulizumab (targeted antibody) for lymphoma

- Naxitamab-gqgk (targeted antibody) for neuroblastoma

- Necitumumab (targeted antibody) for lung cancer

- Nivolumab (checkpoint inhibitor) for bladder, colorectal, esophageal, GEJ, head and neck, kidney, liver, lung, and stomach cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, and mesothelioma

- Obinutuzumab (targeted antibody) for leukemia and lymphoma

- Ofatumumab (targeted antibody) for leukemia

- Panitumumab (targeted antibody) for colorectal cancer

- Peginterferon alfa-2b (immunomodulator) for melanoma

- Pembrolizumab (checkpoint inhibitor) for bladder, breast, cervical, colorectal, esophageal, head and neck, kidney, liver, stomach, lung, and uterine cancer as well as lymphoma, melanoma, and any MSI-H or TMB-H solid cancer regardless of origin

- Pertuzumab (targeted antibody) for breast cancer

- Pexidartinib (immunomodulator) for tenosynovial giant cell tumor

- Polatuzumab vedotin (antibody-drug conjugate) for lymphoma

- Poly ICLC (immunomodulator) for skin cancer (squamous cell carcinoma)

- Ramucirumab (targeted antibody) for colorectal, esophageal, liver, lung, and stomach cancer

- Relatlimab (checkpoint inhibitor) for melanoma

- Rituximab (targeted antibody) for leukemia and lymphoma

- Sacituzumab govitecan-hziy (antibody-drug conjugate) for bladder and breast cancer

- Sipuleucel-T (vaccine) for prostate cancer

- Tafasitamab (targeted antibody) for lymphoma

- Tebentafusp-tebn (bispecific antibody) for melanoma

- Tisagenlecleucel (CAR T cell therapy) for leukemia (including pediatric) and lymphoma

- Tisotumab vedotin (antibody-drug conjugate) for cervical cancer

- Trastuzumab (targeted antibody) for breast, esophageal, and stomach cancer

- Trastuzumab deruxtecan (antibody-drug conjugate) for breast, esophageal, and stomach cancer

- Trastuzumab emtansine (antibody-drug conjugate) for breast cancer

- T-VEC (oncolytic virus) for melanoma

New immunotherapies are being developed and immunotherapy clinical trials are under way in nearly all forms of cancer.

Can people with autoimmune diseases and cancer be treated with immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy has the potential to treat all cancers.

People with mild autoimmune diseases are able to receive most immunotherapies. Typically, autoimmune treatment is adjusted and a checkpoint immunotherapy, such as those targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, is used. However, each patient should speak with his or her doctor regarding the options that are most appropriate.

Can people with HIV be treated with immunotherapy?

People with HIV who are receiving effective anti-viral treatment and whose immune systems are functioning normally may respond to cancer immunotherapy and are therefore eligible to receive immunotherapy, both as a standard of care and as part of a clinical trial.

How can I receive immunotherapy treatment?

The administration and frequency of immunotherapy regimens vary according to the cancer, drug, and treatment plan. Clinical trials can offer many valuable treatment opportunities for patients. Discuss your clinical trial options with your doctor.

How can I tell whether immunotherapy is working?

Immunotherapy treatments may take longer to produce detectable signs of tumor shrinkage compared to traditional therapies. Sometimes tumors may appear to grow on scans before getting smaller, but this apparent swelling may be caused by immune cells infiltrating and attacking the cancer. Many patients who experience this phenomenon, known as pseudoprogression, often report feeling better overall.

In certain cancer types, immune-related side effects may be linked with treatment success—specifically, melanoma patients who develop vitiligo (blotched loss of skin color)—but for the vast majority of patients, no definitive link has been established between side effects and immunotherapy’s effectiveness.

How is the Cancer Research Institute involved in the development of immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy has the potential to treat all cancers.

For over 70 years, the Cancer Research Institute (CRI) has been the pioneer in advancing immune-based treatment strategies against cancer. It is the world’s leading nonprofit organization dedicated exclusively to saving more lives by fueling the discovery and development of powerful immunotherapies for all types of cancer.

CRI provides financial support to scientists at all stages of their careers along the entire spectrum of immunotherapy research and development: from basic discoveries in the lab that shed light on the fundamental components and mechanisms of the immune system and its relationship to cancer, to efforts focused on translating those discoveries into lifesaving treatments that are then tested in clinical trials for cancer patients.

What is cancer immunology?

Cancer immunology studies the relationship between cancer and the body’s immune system, including its innate ability to prevent or eliminate cancer cells, called immunosurveillance. Research shows that the body’s natural defense mechanisms can recognize and target cancer cells. Cancer immunologists focus on developing immunotherapies to boost those natural defenses.

What are immunotherapies?

Cancer immunotherapies also are known as biologic therapy, biotherapy, or biological response modifier therapy, and include checkpoint blockade, cancer vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, oncolytic virus therapy, T cell transfer, and other immune-modulating drugs such as cytokines and other adjuvant therapies. These effective ways for preventing, managing, or treating different cancers can be used in conjunction with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation.

Is cancer immunology a new field of research?

The earliest forms of what would later be considered the start of cancer immunotherapy originated with research done by Dr. William B. Coley (1862-1936), a cancer surgeon and father of CRI founder Helen Coley Nauts. He discovered that “killed” bacteria stimulated the immune system to attack cancer cells. Modern cancer immunology is based on more recent advances in scientific understanding of the immune system’s various components, their function, and their role in cancer control. Cancer immunology is a relatively young field, but advances in treatment are aided by donor support.

Where can I get more information about immunology?

- Read our timeline of milestones in the field.

- Learn what immunotherapy is.

- Discover which immunotherapies are available for different cancers.

- Find out how different types of immunotherapy work.

- Get to know the scientists and patients behind the progress.

- Search for patient-specific resources.

Get more information

Immunotherapy treatment harnesses the body’s natural strength to fight cancer— empowering the immune system to conquer more types of cancer and save more lives.

Antibodies

Antibodies bind to antigens on threats in the body (e.g., bacteria, viruses, cancer cells) and mark cells for attack and destruction by other immune cells

B Cells

B Cells release antibodies to defend against threats in the body.

CD4+ Helper T Cells

CD4+ Helper T Cells send “help” signals to the other immune cells (e.g., B cells and CD8+ killer T cells) to make them more efficient at destroying harmful invaders.

CD8+ Killer T Cells

CD8+ Killer T Cells destroy thousands of virus-infected cells each day, and are also able to seek out and destroy cancer cells.

Cytokines

Cytokines help immune cells communicate with each other to coordinate the right immune response.

Dendritic Cells

Dendritic Cells digest foreign and cancerous cells and present their proteins to immune cells that can destroy them.

Macrophages

Macrophages engulf and destroy bacteria, virus-infected cells, and cancer as well as present antigens to other immune cells.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural Killer Cells recognize and destroy virus-infected and tumor cells quickly without the help of antibodies and “remember” these threats.

Regulatory T Cells

Regulatory T Cells provide the checks and balances to ensure that the immune system does not overreact.

How the Immune System Works

Organs, tissues, and glands around your body coordinate the creation, education, and storage of key elements in your immune systems.

Appendix

Thin tube about 4 to 6 inches long in the lower right abdomen. The exact function is unknown; one theory is that it acts as a storage site for “good” digestive bacteria.

Bone marrow

Soft, sponge-like material found inside bones. Contains immature cells that divide to form more blood-forming stem cells, or mature into red blood cells, white blood cells (B cells and T cells), and platelets.

Gut

Cells lining this set of organs and glands, as well as the bacteria throughout it, influence the balance of the immune system.

Lymph nodes

Small glands located throughout the body that filter bacteria, viruses, and cancer cells, which are then destroyed by special white blood cells. Also, the site where T cells are “educated” to destroy harmful invaders in your body.

Nose

This organ’s receptors detect bacteria and viruses. Nasal mucus catches these pathogens so the immune system can learn to defend against them.

Skin

This organ is not only a physical barrier against infection but also contains dendritic cells for teaching the rest of the body about new threats. The skin microbiome is also an important influence the balance of the immune system.

Spleen

An organ located to the left of the stomach. Filters blood and provides storage for platelets and white blood cells. Also serves as a site where key immune cells (B cells) multiply in order to fight harmful invaders.

Tonsils

A set of organs that can stop germs from entering the body through the mouth or the nose. They also contain a lot of white blood cells.

Thymus gland

Small gland situated in the upper chest beneath the breastbone. Functions as the site where key immune cells (T cells) mature into cells that can fight infection and cancer.

Immunotherapy Matters, for One and All

As a science-first organization dedicated to supporting cancer immunotherapy research, we’re funding a future that fights back against cancer—all with your help.

News and Events

Discover how we are building a world without cancer on our news and events page.

Join CRI in Shaping the Future of Immunotherapy

Support the pioneering work of CRI in advancing immunotherapy.